How sustainable is the platform economy for Europe?

Digital online platforms have gained a lot of attention in recent years. From platforms for taxis in the case of Uber to micro-task allocation by Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: mostly non-European companies penetrate an increasing amount of sectors. In the public debate, working conditions of platform workers and tax avoidance of tech companies have been particularly high on the agenda. European Commission President-elect, Ursula von der Leyen, announced she “will look at ways of improving the labour conditions of platform workers, notably by focusing on skills and education ». Today, the contribution to, or mitigation of, climate change is being brought to attention by the digital industry and civil society. In this article, we will give a short overview on what platforms are, what they offer in terms of employment and how their environmental impact can be assessed.

Digital online platforms often constitute hybrid marketplaces matching supply and demand and offering further services or products. Due to the fact that both sides are not always charged in monetary terms (but with data for instance), the marketplace can better be pictured by using a multi-markets approach, where each side can be subject to different market dynamics.

Platforms often benefit from direct and indirect network effects that constitute their and their users’ value. These network effects make it very difficult for new entrants to establish themselves, thus posing challenges to antitrust policy. Direct network effects designate the utility of users when the number of other total users increases, while indirect network effects imply that the increase on one side of the platform attracts more users on the other. Network effects can create switching costs when moving to a competing platform, leading to lock-in effects which may constitute competitive advantages. In the case of Facebook for instance, messages, photos and friends would be lost in case of switching. From an anti-trust point of view, the transferability of data and interoperability are particularly important. Platforms are also characterised by a high proportion o

f fixed costs, particularly related to R&D activities, and relatively low variable cost and marginal costs for new users.

When it comes to the differences among platforms, a relatively exhaustive typology of digital platforms has been offered by Evans and Gawer (2016). They distinguish between:

- “Transaction platforms such as eBay, Tencent and Uber, facilitate transactions between users that would be impossible or difficult to establish otherwise. eBay makes it possible for a US resident to find and buy products from a Chinese resident.

- Transaction platforms create multi-sided markets as they promote interactions between different groups of users (e.g. individuals or companies as buyers and/or sellers).

- Innovation platforms are technological building blocks that support the development of complementary services or products by users. An example is the iPhone, for which anyone can develop an application (app).

- integrated platforms are platforms that combine features of transaction and innovation platforms (e.g. Google/Alphabet)

- Investment platforms include companies that have developed a platform portfolio strategy and act as a holding company, active platform investor or both such as Priceline Group.”

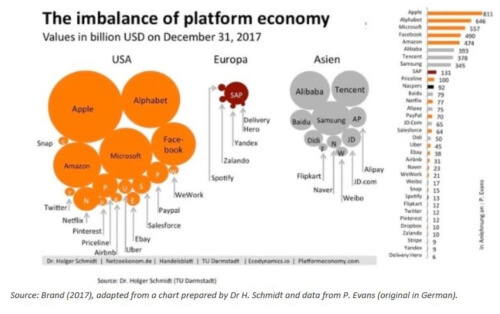

In comparison, Europe has relatively few digital champions with a high market value. On the stock markets, US-American and Chinese companies top the list of the world’s most valuable companies. Due to the rapidly changing nature of the sector and the possibility to substitute services rather quickly, these evaluations may prove to be insufficient to account for the real weight digitalisation has in Europe’s economy. With its strong industrial base and decentralised markets, European digital companies are active in a wide array of sectors and different degrees of integration with the ‘real economy’, as the concept of ‘industry 4.0’ highlights. Since some tech giants however question the European labour model and do often not contribute to taxation the same way ‘traditional’ companies do, more and more policy-makers are aiming at regulation and/or introducing anti-trust cases. The European Commission, as the EU’s antitrust watchdog, has already issued multi-billion euro fines against Microsoft and Google.

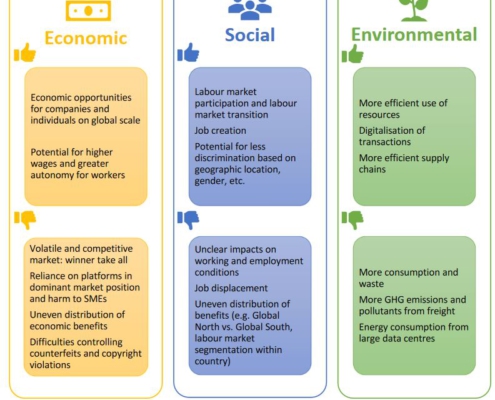

But how sustainable are these platforms economically, socially and environmentally speaking?

Let’s first take a look at the economic benefits and risks platforms can bring to the EU economy. From a theoretical point of view, platforms create more transparent markets, improve allocation of and access to goods and services and may contribute to productivity gains (at macroeconomic level however, productivity is stagnating). In its assessment of online platforms, the European Commission however detected the existence of potentially “unfair” trading practices imposed by these intermediaries: unfair terms and conditions; refusing market access or unilaterally modify the conditions for market access, promoting their own services unfairly, inserting unfair “parity” clauses and lacking transparency. Furthermore, platforms do not disclose the design of their search tool, which poses the question of implicit bias towards minorities. At EU-level, there has been also a debate about the introduction of a “digital tax” since many of these platforms have chosen their company seats in what some have called tax havens.

In March 2018, the Commission had therefore proposed new rules to ensure that digital business activities are taxed in a “fair and growth-friendly way” in the EU. Since, there has been no agreement by member states.

The EU has also introduced platform-to-business regulation last July, foreseeing that online businesses should justify when they decide to terminate business relations and are required to disclose how businesses are ranked on their platforms. The measures will impact a range of platforms that use ranking structures in their user-interfaces, such as Airbnb, the Apple App Store, and Booking.com (Dutch company now owned by Priceline).

When it comes to platform work, the largest and most recent European survey on the topic in 16 EU Member States found that around 2% of the adult population do platform work as their main job, while another 10% do it at various levels of intensity and frequency next to other activities. Most people working for platforms are contractually considered independent by the platform. In average, platform workers are disproportionately well educated, with majorities of college-educated providers on most platforms (Schor et al. 2017). However, different patterns and needs are visible when comparing these workers. While the easy access to labour and flexible working provisions are seen as advantages by most platform workers, some dependent workers (that is: people working mainly for a platform) find themselves in a position of extreme precariousness without access to social protection.

Few of dependent platform workers earn more than poverty wages without being able to access alternative forms of employment.

In the US there is growing evidence that the platform economy is fostering racial discrimination, via the peer-to-peer structure of the exchanges. Harvard researchers found that Airbnb hosts were 16% more likely to refuse to rent to guests with African-American sounding names.

The establishment of the European Pillar of Social Rights may improve the particular situation of the formally independent, but de-facto dependent platform workers by granting access to social protection, if implemented by member states. Furthermore, member states have progressed to varying degrees in adapting platform work to their legal system. Some countries like Belgium have created a special tax regime with limited effectiveness.

The platforms’ environmental impact is today insufficiently clear due to the unwillingness of these platforms to share data and the difficulty in accounting the complex supply chains. Platforms can in theory more efficiently allocate resources, share resources and reduce transaction costs. However, due to the rebound effect (gains in efficiency lead to lower prices, ultimately increasing consumption) and the quantity of energy, often from fossil fuels, the overall impact on our natural environment is somehow more ambivalent and dependent on the business model of the platform and the sector.

In transport, a study on ride-hailing companies in the USA has found that 49-61% if trips would not have been made, had the platform not existed. The same study also found that there was no reduction in car ownership.

According to Click Clean, a campaign launched by Greenpeace, both Apple and Google have the highest share of renewable energies. Factors other than energy were not included in the comparison.

The least transparent companies such as AWS, Tencent, LG CNS, and Baidu are also among the most dominant in their respective markets, and had the worst energy ranking in the comparison. According to the peer-reviewed journal Nature, the ICT industry accounts for more than 2% of global emissions – the same share as the aviation industry. Video streaming is a tremendous driver of data demand, with 63% of global internet traffic in 2015, and is projected to reach 80% by 2020.

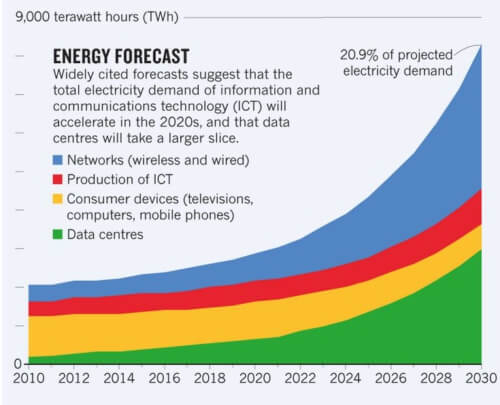

Considering the growing world population and the projected growth in energy demand (see graphic), a debate on how to limit the environmental impact of platforms, but also to uphold European labour standards, is more than necessary. Policy-makers can create the right incentives for the European digital landscapes by favouring decentralised and sustainable solutions compatible with the European market structure. Platforms like BlaBlaCar are often cited as examples for a European digital approach.

Read more

Platform Workers in Europe. Evidence from the COLLEEM Survey, Joint Research Service of the European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/sites/jrcsh/files/jrc106299.pdf

Sustainability in the Age of Platforms, CEPS: https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Sustainability-in-the-Age-of-Platforms-2.pdf

Platform economy: maximising the potential while safeguarding standards? Eurofound: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef19045en.pdf

Schor, J. and W. Attwood-Charles (2017), ‘The Sharing Economy: Labor, Inequality and Sociability on for-Profit Platforms’, Sociology Compass